Do computers dream of imaginary numbers?

Table of Contents

Introduction #

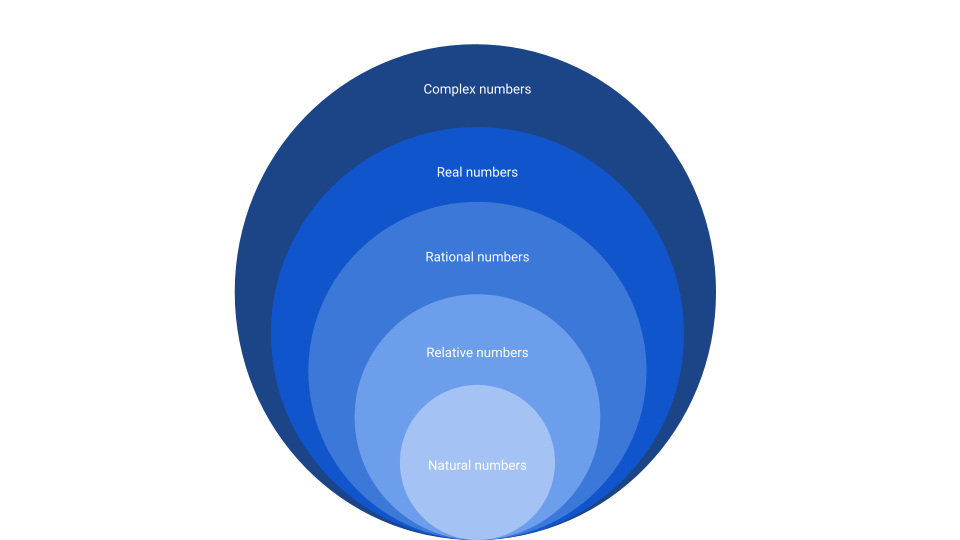

If you followed mathematics courses you’re probably aware there are several types of numbers. Natural numbers (also known as positive integers), relative integers with which comes the notion of negative numbers, rationals which are a ratio of two relative numbers (🤯), irrationals which can’t be expressed as a fraction (like \(\pi\)), reals which are the union of rationals and irrationals, and finally complex numbers which can be seen as a pair of two reals.

However when starting coding, one may find those abstractions lacking and instead encounter weird types such as in Golang: uint8, int32 or float64. In this first article about computers and mathematics, let’s try to understand what they mean and how they relate to “actual” numbers.

Base 2 #

First we need to realize that computers are just a bunch of switches connected together in a smart way.

A switch can be in one of two states: open or closed, which computer scientists chose to name 0 and 1. Some people also call them false and true, which makes more sense when working with propositions rather than numbers.

One can combine multiple switches to store a sequence (or vector) of bits, that is to say, an ordered list of 0 and 1. For instance 01010111 is a sequence of 8 bits. For historical reasons, a sequence of such a length is called a “byte”.

And then comes a very interesting result thanks to euclidian division: any natural number can be expressed as such a sequence. Think about it, let’s take a number like \(13\). If we divide it by \(2\), we obtain \(13 = 2 * 6 + 1\). If we decompose \(6\) itself, we obtain \(13 = 2 * (2 * 3) + 1\) and by decomposing \(3\) itself we get \(13 = 2 * (2 * (2 * 1 + 1)) + 1\). Once developped and grouped by power of two we obtain \(13 = 2^3 + 2^2 + 1\).

Start seeing a pattern here? Let’s write the same expression again but showing all powers of two:

\(13 = 1 * 2^3 + 1 * 2^2 + 0 * 2^1 + 1 * 2^0\)

What if we only took the ones and zeros from the previous expression and put them in a list?

We’d get 1101. Et voilà, we wrote our initial number, \(13\), in a different writing base, in this case, in base 2 🎉!

Note that you can use many different bases to write a number but since computers can only understand open or close switches we are only interested in base 2!

1011 which is named least significant bit (LSB) notation.The operation of taking a decimal written number and transform it in a base 2 number can be reversed. If we take our previous byte 01010111, we can compute it as:

\(0 * 2^7 + 1 * 2^6 + 0 * 2^5 + 1 * 2^4 + 0 * 2^3 + 1 * 2^2 + 1 * 2^1 + 1 * 2^0 = 87\)

Natural integers #

Thanks to this ground work definition we can now work with any natural number! Right?

Right?

Well the thing is computers have limited resources. You can’t write numbers bigger than the maximum number of switches you have available. Most electronic chips are designed to handle numbers with the following sizes:

- 8 bits (aka a “byte”): this is the smallest size available on most computers.

- 16 bits

- 32 bits

- 64 bits: this is the biggest size available.

Those are often available under types such as unsigned integer <N> or uint<N> with N being one of 8, 16, 32 or 64.

You can always write a number with more switches than it takes to store it: just add zeros to its left until you reach the right size. For instance 13 is represented as 00001101 on a single byte.

However you can’t write a number with less switches than it’s base 2 size and expect things to work well! This may sound like an edge case but think about operations like multiplications. If we wanna stay on a byte only and multiply 10000000 and 10111010 together, the result won’t fit! This is what is called an integer overflow.

However with 64 bits, you can store numbers as big as \(18 446 744 073 709 551 615\) which should be able to cover most of your use cases 😁

Relative integers #

What about negative integers?

One simple way of supporting them would be to add one extra bit to natural integers to indicate their sign. In this case, \(13\) would be spelled 000001101, and \(-13\) 100001101.

That works but this is not super convenient, our microships can’t really handle 9-bits numbers… 🤔

Ok, let’s keep 8-bits numbers (or multiples of 8-bits) but use their first bit as a signing bit. We won’t be able to store relative numbers as big as natural ones (this covers \(\rrbracket-128;128\llbracket\) instead of \(\rrbracket-256;256\llbracket\)) but it’ll be easier for everyone. In this case \(-13\) writes as 10001101.

It’s better but what about 0? With this schema, both 10000000 and 00000000 would be acceptable notations. This is a bit awkward…

Hopefully, there’s a solution named the two’s complement method.

WIP

Relative integers are often available under types such as integer <N> or int<N> with N being one of 8, 16, 32 or 64.

Rational numbers #

We could write rational numbers as a couple of two relative numbers, the numerator and the denominator. However this writing would be unique only if those two numbers are coprime. This would put a lot of responsabilities on the developer to put the right numbers ahead of time. Instead we’ll just try to use the same method to describe all real numbers.

Real numbers #

As we already emphasized, computers have finite resources. And therefore, they can’t describe or manipulate numbers with an infinite sequence of digits. So basically, computers can’t reason about \(\frac{1}{3}\) or \(\pi\).

However they can reason about an approximated value with a certain error margin. Here comes a notion well known by physicists: scientific notation.

$$ \pi \approx 3.14159265*10^0 $$

$$ \frac{1}{3} \approx 3.33*10^{-1} $$

The trick is basically to separate a number in two parts:

- a mantissa which stores the significant digits for the number.

- an exponent which stores the power of \(10 \) to apply to the mantissa to “shift” the comma to the right position.

This is why they are called floating numbers, the comma is “floating” in the mantissa according to the exponent’s value.

Both the mantissa and the and exponent can be stored as signed integers, but that does not mean the same thing:

- if the mantissa is negative, the number is negative

- if the exponent is negative, the number belongs to \(]-1;1[\)

People agreed on the IEEE 754 standard to define the length of the mantissa and exponents. Two formats emerged, to accomodate different bit sizes:

- 32 bits floating numbers: 23 bits mantissa + 1 bit to indicate the number’s sign + 8 bits exponent

- 64 bits floating numbers: 52 bits mantissa + 1 bit to indicate the number’s sign + 11 bits exponent

And yes the sign is actually stored in a dedicated bit so we can define \(0\) in two different ways which is weird. The format also supports special values to indicate \(\infty\) and \(-\infty\) or an indeterminate form (often called NaN for “Not a Number” in computer science).

Anyway, with those two new types at hand (float32 and float64 in Golang for instance) one can describe numbers in \(]-3.4 * 10^{38} ; -1.2 * 10^{-38}[ \cup \{ 0 \} \cup ]1.2 * 10^{-38} ; 3.4 * 10^{38}[\) and \(]-1.8 * 10^{308} ; -2.2 * 10^{-308}[ \cup \{ 0 \} \cup ]2.2 * 10^{-308} ; 1.8 * 10^{308}[\) respectively.

Complex numbers #

We’re close to the end of our journey! There’s one last category of numbers. They’re not pretty common but are powerful enough to deserve a mention here: complex numbers. They are not called this way because they are difficult to understand but rather because they work like a complex composed of two units, a real part and an imaginary one. And therefore, a complex number can simply be seen as a pair of two reals.

Usually, programming language don’t support complex numbers by default so you have to import external libraries or define them yourselves as a new composite type:

type complex64 struct {

real float32

imaginary float32

}

Then it’s up to you to define operations on them!

complex64 (two float32s) and complex128 (two float64s) types.Conclusion #

Wow, that was a lot! Let’s do a quick recap:

- computers can only “understand” natural numbers written in base 2 because they are just a bunch of switches.

- mathematics are not limited by the physical world: imagination (and therefore coffee ☕) is the only limit! When dealing with computers, you always need to take into account the hardware you’re working with.

- relative numbers require a small trick to be efficiently understood by computers: the two’s complement method.

- real numbers are lies, they can only be stored as approximated values.

- with all these primitives established, one can build more abstractions such as complex numbers, vectors, whatever you want really!

In the next post, we’ll talk about another interesting mathematical beast: functions!

See you next time 👋